DAR ABDUL AZIZ AL ROWAS

The term “Dar” in the Arabic language is used to describe residential buildings. Although many of the terms referring to residences are used interchangeably, “Dar” is a term specifically used to describe both the main building and its associated surroundings.

Dar Abdul Aziz Bin Mohamed Al Rowas is the private residence of Sheikh Abdulaziz Al Rowas in Salalah, the provincial capital of Dhofar, the southernmost region in the Sultanate of Oman. The unifying vision and driving force were provided by Sheikh Abdul Aziz’s late wife, Aida Al Khaled Al Rowas.

The Dar is located in Salalah, Sultanate of Oman.

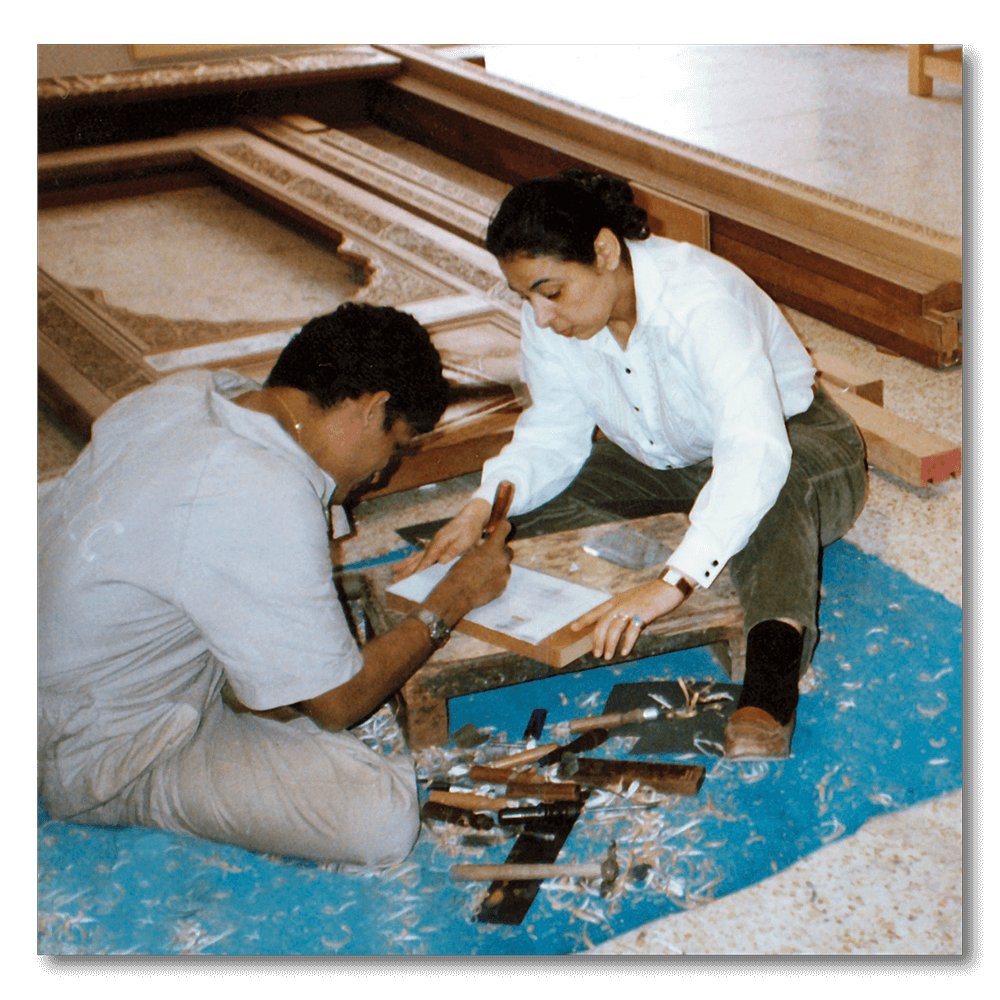

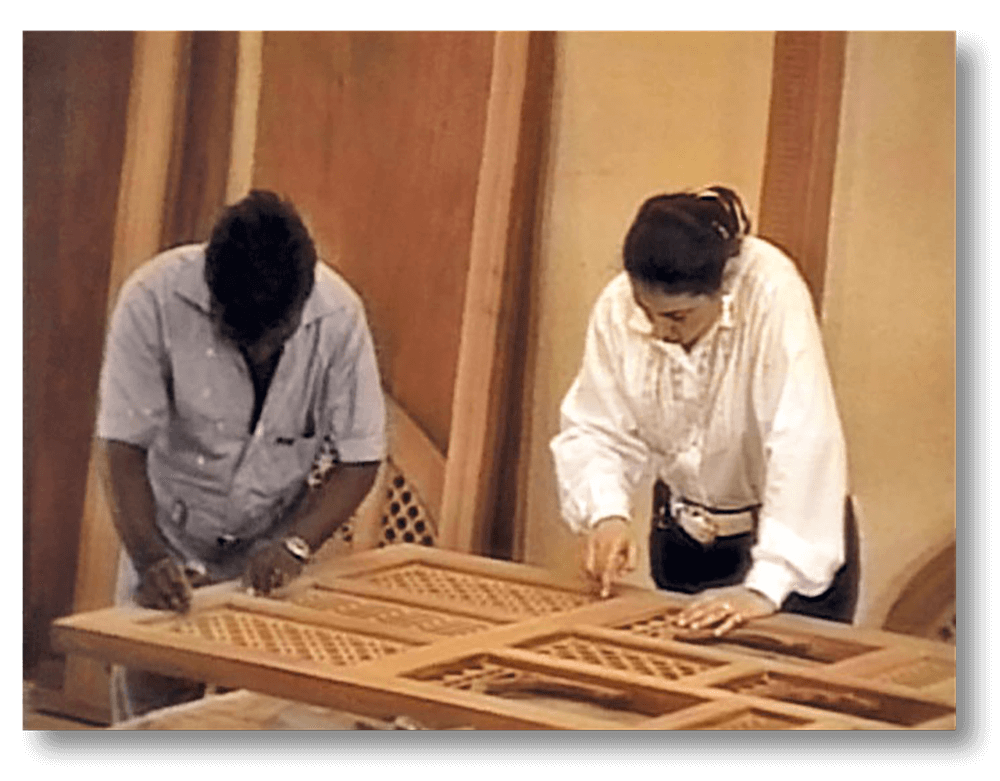

From the conception stages, Aida Al Rowas outlined the design concept for the building’s architecture and interior design. She was able to achieve this by directly managing the purpose-built woodworking workshop herself, and the construction site, through a specialized private company setup specifically for this task. She also relied on the support of a civil engineering consultant to ensure that all the technical calculations were correct and adjusted the designs and their execution to accommodate these requirements as the work progressed. Her dedication ensured that a single unifying vision permeated every aspect of the final structure, fully realized her design concept, and achieved unprecedented harmony and balance in the final interior and exterior design of the building.

Aida Al Rowas worked closely with every aspect of the project. The core team consisted of a draftsman, accountant, masons, carpenters, carvers, polishers and helpers. The size of the operation varied throughout the work with a maximum of 70 workers towards the end of construction.

The design concept, presented in her book Silent Journey, was underpinned by key components that guided its application to all aspects of the final residence, namely

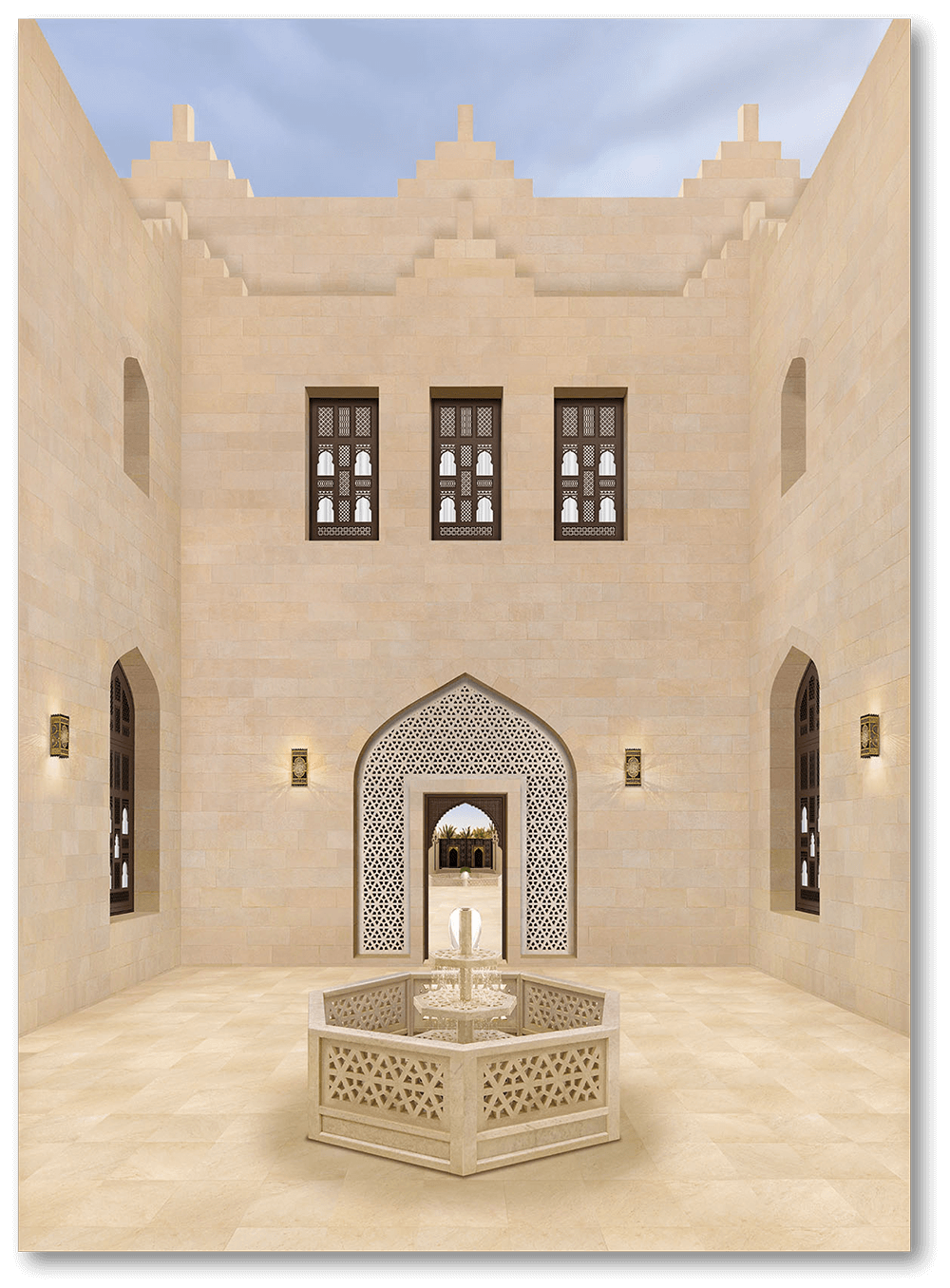

1. Preserving the elevation and style of traditional Dhofari architecture and reliance on the use of natural materials in the finish of the building.

This included exclusive use of natural stone and Omani marble to clad the interior and exterior elevations, floors and ceilings. The use of natural materials together with the layout and strategic use of space and apertures played a major role in temperature regulation in traditional Dhofari residences. This regulating effect can also be observed in the ‘Dar’ (Al Dar) today.

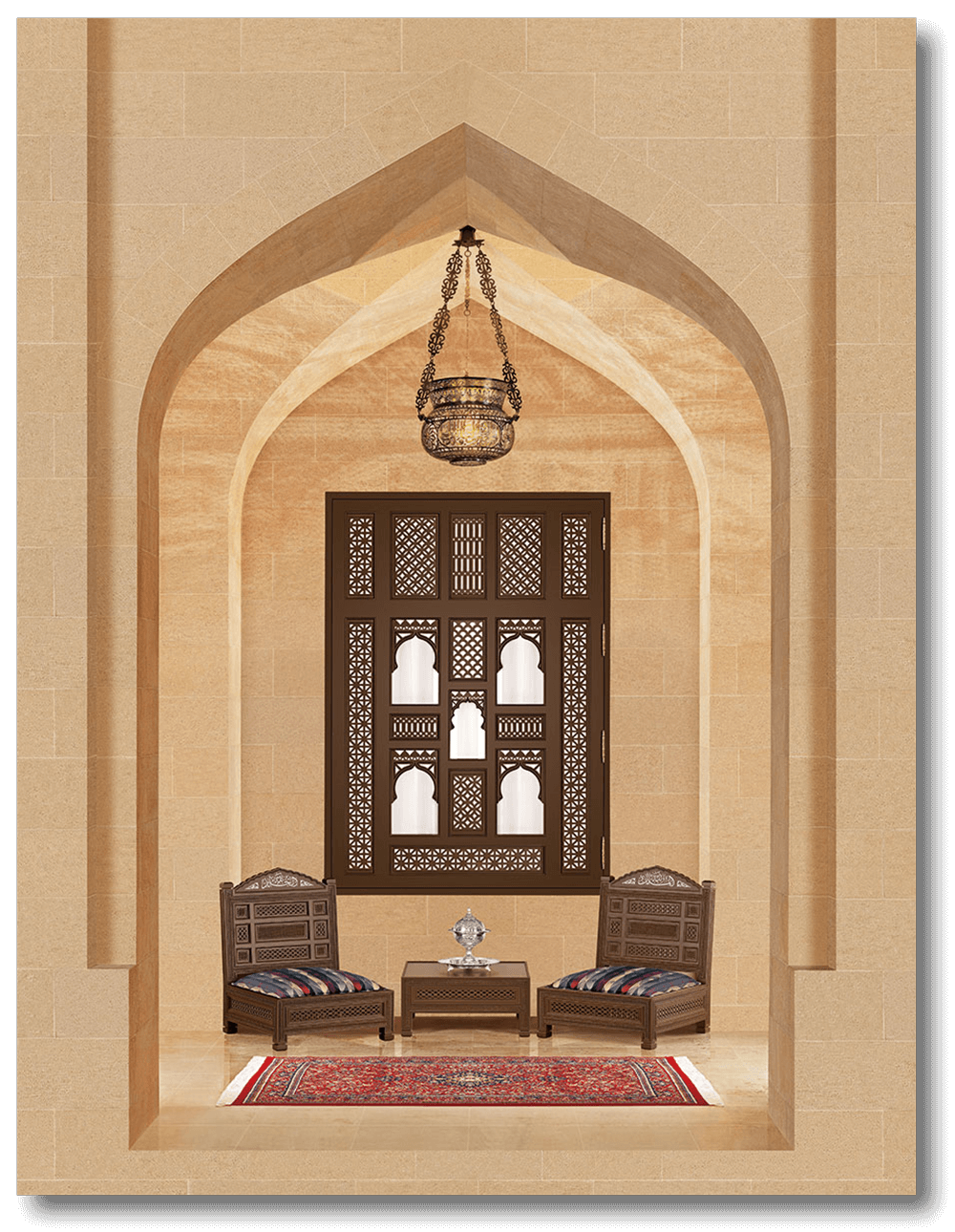

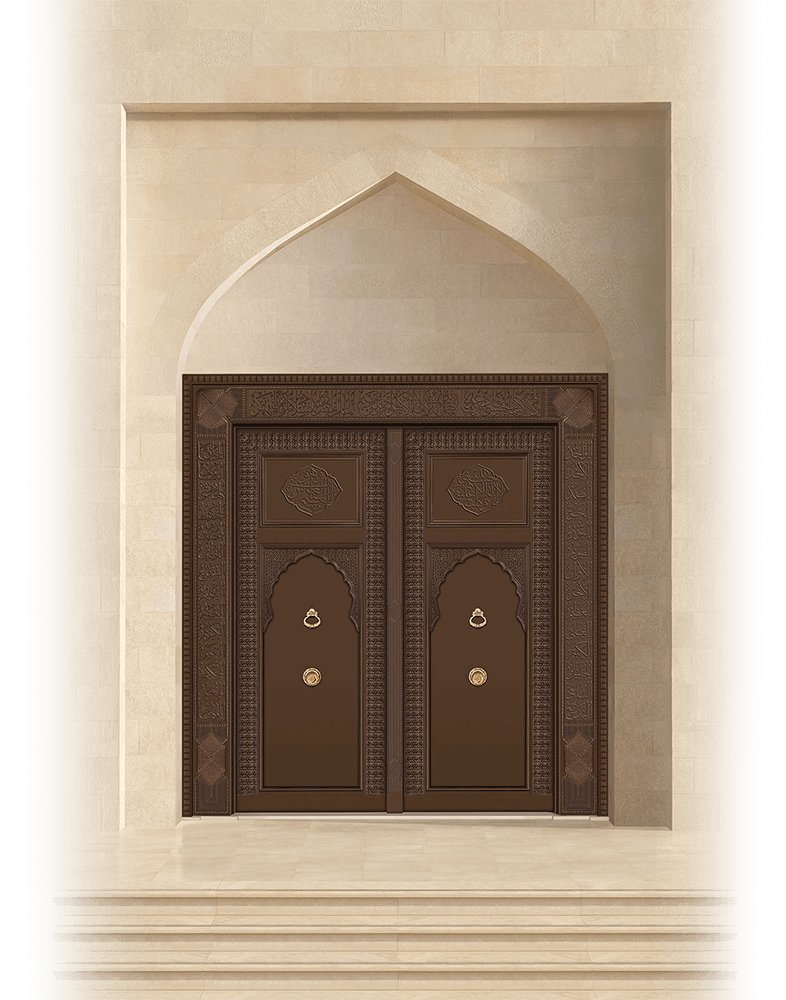

2. Showcasing the traditional wooden ornamental Dhofari window and preserving its breadth and apertures.

3. Selecting verses from the Qur’an as the central focal point of the hand-crafted wooden ornamentation, featured throughout the building.

4. Relying on geometric patterns to showcase the Qur’anic verses inscribed on the ornamental timberwork.

Previously, intricate geometric patterns in Islamic art were more commonly found etched on metal, drawn on illustrated manuscripts or moulded in plaster. Woodcarving was more usually associated with decorative botanical motifs; decorative geometric motifs when etched on wood in Islamic art, were typically substantially larger in scale and comparatively simpler in design than those developed and hand-crafted exclusively for Dar Abdul Aziz bin Mohamed Al Rowas.

Bringing the vision from paper to woodwork was a collaborative process. Aida Al Rowas spent time with the carver for each pattern to help them translate her vision. An iterative process involved many samples until the final result was approved to apply to the solid Brazilian mahogny wood that most of the house has.

The decision to draw on and preserve key elements of Dhofari heritage was made all the more urgent at the time since the traditional architecture of Dhofar was under serious threat, with historic Dhofari houses disappearing and giving way to modern structures instead. Many buildings featured in the photographs taken by Aida Al Khaled Al Rowas during her trip to Oman in 1977 and published in her books Silent Journey and Oman: Faces and Places 1977, are long gone. She was also greatly inspired by the distinctive Dhofari window, and considered it a crucial design ‘seed’ across spaces in the residence, as its aesthetic relied on several simple geometric forms, capable of combining to produce a variety of patterns and frames.

Going beyond preserving traditional Dhofari architecture, was the goal of setting the building within a modern Omani identity grounded in its heritage and interconnected with its broader Arab context. Here, choosing specific styles of decorative arches found in the traditional Dhofari window and more broadly in Arab Islamic architecture, and the prevalent tradition of inscribing verses from the Quran and their prominent display above entranceways in Oman and elsewhere, were the primary points of connection between traditional Dhofari architecture and its broader Omani, Arab and Islamic context.

Aida Al Rowas overseeing the quality of sanding to prepare the wood for polishing. Minute attention to detail while maintaining the big picture was the Gestalt approach that made the completion of this Dar possible.

A key component of her design philosophy was a rejection of repetition, and the promotion of evolution and maturity of design in Islamic art. Although she was greatly inspired by the Dhofari windows that she had photographed, she also designed numerous new forms inspired by it that can be found throughout the residence.

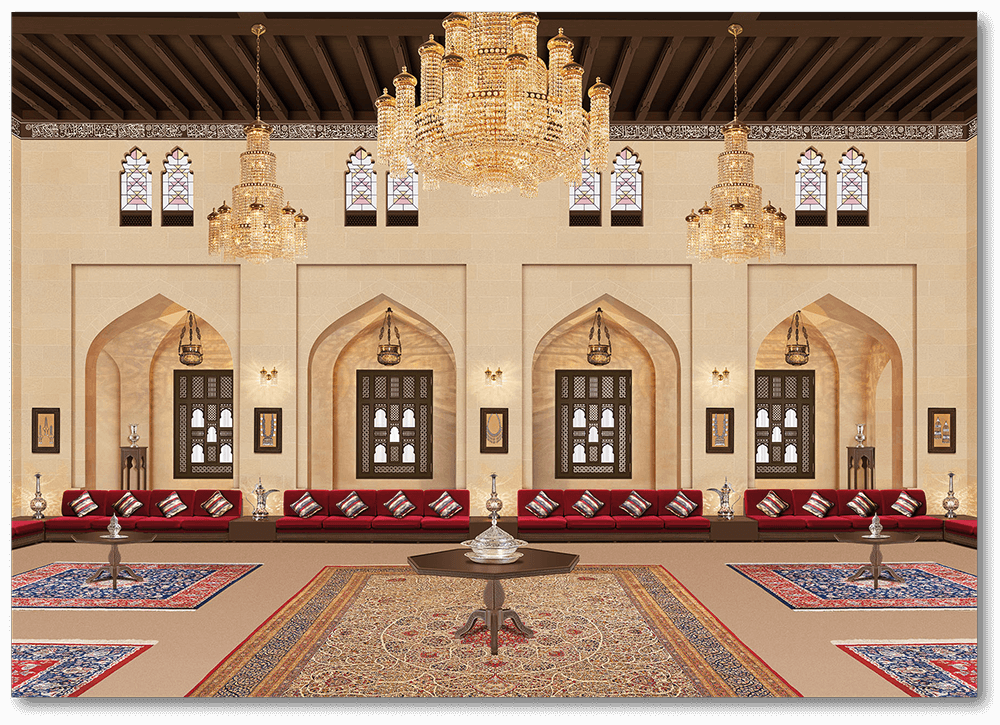

The incorporation of challenging architectural features throughout the structure creates additional albeit subtle points of connection to Arab and Islamic architectural tradition. These range from stone-clad four-arched groined vaults, which form the arcades framing the main reception hall, to decorative stone-clad arches and recessions, built to exacting proportions, thereby creating varying points of emphasis and atmospheres in each space. These design elements, together with the deft incorporation of the broad tradition of displaying select Quranic verses embellished with artistic ornamentation to decorate interior spaces, highlight a deep and nuanced understanding of and engagement with aesthetics and proportions in Islamic art and the underlying philosophy.

The dhofari window in a vault with uniquely designed chairs and a table for this particular corridor in the main majlis (Presence Hall). The vaults are quite the complex achievement from a civil work perspective. Every aspect of design, furnishings, carpets, lights fixtures and fabric were designed and executed by Aida Al Rowas. The finished work maintains the soul of the traditional stone and wood structures while sustaining a fully functional household.

The courtyard is inspired by tradtional Damascean houses. Dhofari houses did not usually have a fountain in the courtyard. The seven star shape of this fountain is unique to this house as six and eight sided stars are more easy to render and more common throughout islamic architecture. The arches “Goose neck shape” were standardized in the courtyard area for windows and doors. The patio and main doors are open to reveal the second fountain in front of the main entrance door. Attention to proportions from every angle is a hall mark of this Dar.

To produce the motifs and patterns she herself had evolved, and her dedication to their continued refinement, Aida Al Khaled Al Rowas had to work extremely closely with her draughtsmen, carpenters, wood carvers and polishers. They had to produce custom tools and processes to prepare and carve the intricate geometric patterns that she had designed on timber. As a result of this effort, she managed to successfully standardize the techniques and process of production for the geometric ornamentations and the inscriptions for the selected Qur’anic verses for the entire project. This ensured that various carvers and carpenters over the years were trained to replicate the required patterns every time, down to the millimetre scale. All the beams, windows, doors, cupboards, friezes and the main ornamental wall-hangings inscribed with Qur’anic verses were completed in record time, with a relatively small close-knit team.

The corridor leading to the main hallway remains filled with natural light from the courtyard. The niches are intriquately designed with great attention to detail to match the patterns on the door and this rendition of the dhofari window. Natural stone and solid mahogony wood are the materials used. Silver pots on top of the niches are an echo of how dhofari families displayed wealth by displaying china pots on top of niches inside the house.

Given, the harmony, beauty, and simplicity of the final result, it became apparent that the furniture of the house had to also adhere to the exact standards applied to the architecture of the building and its main aesthetic features. In the years that followed, Aida Al Khaled Al Rowas, in the same carpentry workshop, designed and manufactured all the furniture and interior features of the house, with each piece being made specifically for the place it currently resides in.

In recognition of the importance of this work and its cultural value, and in response to a request by its owner, Dar Abdul Aziz Bin Mohamed Al Rowas was designated as a heritage trust with the approval of the late Sultan Qaboos and His Majesty Sultan Haitham bin Tariq, who was the Minister of Heritage and Culture at the time, and the Minister of Endowments and Religious Affairs (2012); Sheikh Abdulaziz and Aida Al Rowas were granted the right to use and administer it throughout their lifetime, and their daughters Dr. Sora and Dr. Meda were named as its guardians after them and tasked with assigning their successors in this role.

The main hallway showcases many elements mentioned in the text. The high ceilings, arches, brochard textiles and stained glass in sky windows are a marraige between Dhofari and Damscean architecture. The attention to harmony, function and form informed every angle of the design of this hallway.

Operation failed.Please try again.

Operation failed.Please try again.